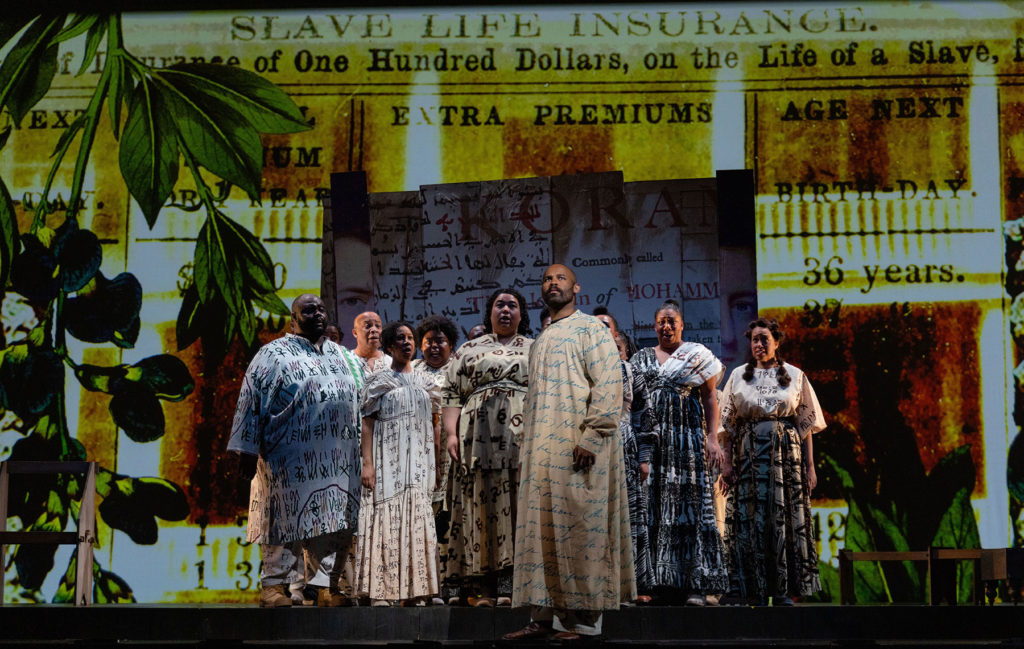

JAMEZ MCCORKLE C. AS THE TITLE CHARACTER IN BLOS OMAR. PHOTO BY OLIVIA MOON PHOTOGRAPHY

Presented by Boston Lyric Opera, co-produced by Spoleto Festival USA and Carolina Performing Arts at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Music by Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels

Libretto by Rhianon Giddens

Conducted by Michael Ellis Ingram

Directed by Kaneza Schaal

Inspired by Dr. Ala Alryye’s translation of Mar ibn Said’s autobiography in his book, A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar Ibn

Published by and presented with permission of Subito Music Corporation

Emerson Cutler Majestic Theater

219 Tremont St, Boston, MA 02116

May 5 – 7, 2023

WCRB recorded a performance of BLO’s production for an episode of WCRB in Concert that will air in fall 2023. Sign up for recording broadcast updates here.

Critique by Maegan Bergeron-Clearwood

BOSTON, Mass. —

This past Saturday night, I was witness to a conjuring. Omar, a new opera co-created by Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels, is not just in conversation with history. It brings the past to life by filling in the gaps of archival memory and giving voice to a narrative that has otherwise slipped through the cracks of history.

Until now, the story of Omar ibn Said has largely been contained to academic circles, where it holds a critical place as the only known surviving account of United States slavery to have been written in Arabic. From this account, we know that Omar was an accomplished and devout Islamic scholar in present-day Senegal, when, at 37 years of age, in 1807, he was captured, transported to Charleston, South Carolina, and sold into slavery.

The audience for Omar’s 14-page autobiography was his Christian captors, so there are gaps in the narrative and only a limited glimpse into his interiority (although scholars have theorized that he might have been writing subversive truths between the lines). Omar fills in these gaps with inventive narrative devices, in the form of characters and otherwise missing scenes, but also metaphor, ghosts, and lyricism.

The result is a story that is expansive in both scope and depth, taking us from the physical horrors of colonial violence to the most intimate corners of Omar’s psyche. It is complemented by an equally robust score, which seamlessly integrates musical influences from across geographic and temporal lines, from West African folk music to Islamic spiritual melodies to American bluegrass and jazz motifs.

One of the most evocative instances of this imaginative meaning-making takes during the Middle Passage, early in the first act. This is a missing chapter in Omar’s written autobiography (a choice likely meant to whitewash his story for his readers), so Giddens and Abels give it ample life onstage. Omar (Jamez McCorkle) is mostly silent here, bearing witness with the audience as fictional – but also very real – characters tell their stories of lost mothers, lost languages, and lost names.

Violence in this scene and throughout the production is represented rather than reproduced; instead of prop chains and whips, there are stylized projections and set pieces. This attention to care, with a focus on human connection, is what distinguishes Omar from being a gratuitous retelling of historical trauma into something active, purposeful, and dramaturgically satisfying.

A small part of me wrestled with this aspect of Omar: what does it mean to make sense out of something inherently and utterly senseless? A few moments in this adaptation seemed to flatten aspects of Omar’s story for the sake of giving it a neat and tidy dramaturgical arc, particularly the false distinction between “bad” (overtly violent) and “good” slaveholders.

JAMEZ MCCORKLE C. AND THE CAST OF BLOS OMAR. PHOTO BY OLIVIA MOON PHOTOGRAPHY.

Midway through the story, Omar escapes from a sadistically cruel master and is bought by a man whose slaves are so happy that one of them chooses to return to his farm, a man who exotifies and attempts to convert Omar to Christianity; the text does little to directly name this violence. During my experience this weekend, these choices felt especially questionable given the overwhelmingly white audience (myself among them) for whom its mostly Black cast was performing.

But overall, Omar is a story about the act of storytelling. Julie (played by an exceptional Brianna J. Robinson), a fictionalized character who serves as one of Omar’s guides, tells him that lingering on histories, memories, and feelings is not shameful: it is healing. Omar as a historical figure has been framed as exceptional, someone whose story deserves to be memorialized, but in the operatic adaptation of his life, it is clear that every voice that was lost to the violence of slavery was exceptional. In telling Omar’s story this way, in listening to the silences between the lines, the act of storytelling becomes an act of life and liberation.

In someone else’s hands, Omar might have been a ghost story: a long-dead historical figure is written into a script and interpreted onstage. But in the hands of Giddens, Abels, and Schaal, Omar is a séance. Omar’s spirit, with a host of others, was alive last Saturday night.

Omar has finished its brief New England run on Sunday, but it was recorded a for an episode of WCRB in Concert that will air this fall; sign up for BLO’s email list for updates (I cannot recommend doing so enough!).