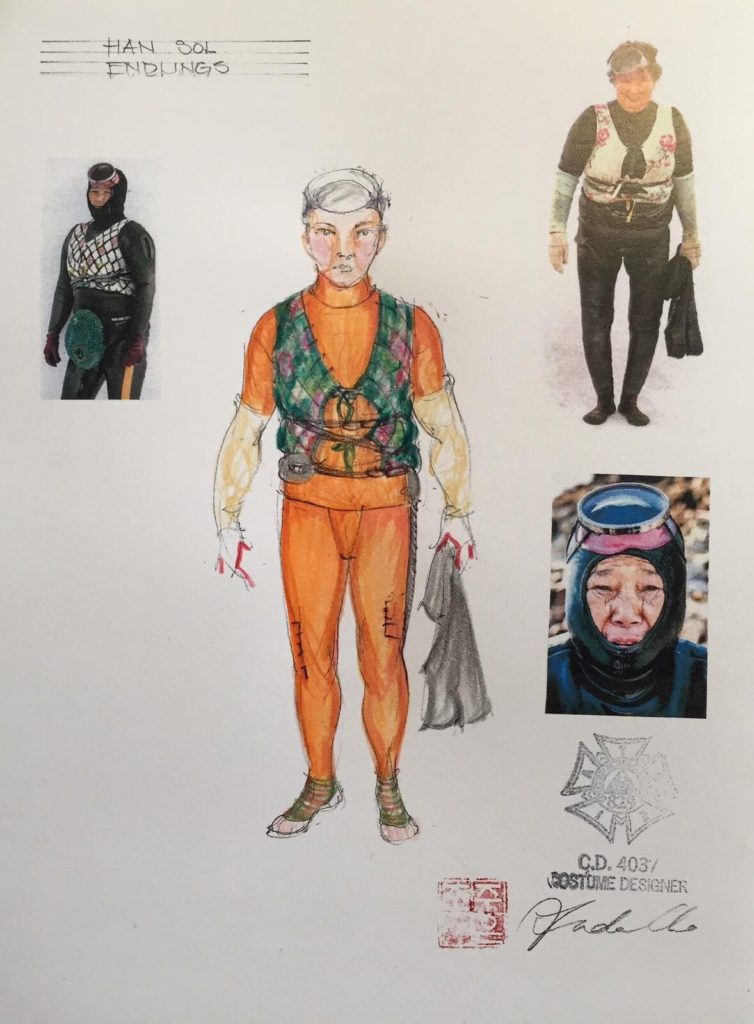

Han Sol Dive Suit Costume Rendering by Linda Cho

A Conversation with “Endlings” Playwright Celine Song

Presented by American Repertory Theatre

By Celine Song

Directed by Sammi Cannold

February 1 – March 17, 2019

ASL Interpreted performances: Wednesday, March 13 at 7:30PM and Sunday, March 17 at 2PM

Open Captioned performances: Thursday, March 14 at 7:30PM and Saturday, March 16 at 2PM

Audio Described performances: Friday, March 15 at 7:30PM and Saturday, March 16 at 2PM

Loeb Drama Center

Cambridge, MA

7till8 Wetsuits on Facebook

OpEd and interview by Diana Lu

They are sometimes called “Korean mermaids,” and sometimes “sea women,” or haenyeo. The female free divers of Jeju Island are the last keepers of a centuries-old tradition of ocean floor fishing, one that created a unique matrilineal craft and matriarchal economy. In the 1960s, there were more than 26,000 haenyeo. Today there are less than 4,500. Nearly all are over 50 years old, with few young women interested in replacing them. It is difficult, dangerous work, diving without oxygen, wearing lead weights for up to two minutes at a time. About nine haenyeo a year are lost to the sea.

Some enjoy the work and the independence it has always afforded them and mourn the loss of their way of live. Others dive grudgingly and are glad to send their daughters to be educated in the city. Either way, it is understood that theirs will be the last generation of haenyeo. Perhaps that’s why in recent years, there have been multiple efforts to document their stories.

The Jeju government built the Haenyeo School and Haenyeo Museum, and in 2016, UNESCO inscribed haenyeo to its Intangible Cultural Heritage list. The year before, photographer Hyung S. Kim created a photo gallery displayed at the Korean Cultural Service in New York. And a few years ago, an episode of a Korean documentary series called “Three Days,” in which the crew spent three days with the haenyeo on the island of Man-Jae, inspired Celine Song to write her acclaimed new play, “Endlings,” soon to be produced for the first time by the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I am reading everything I can find about haenyo in preparation for seeing “Endlings.”

It can be said that the haenyeo live in two worlds. Everyday, these women straddle the thin line separating land and sea, life and death, a past in which they thrived and a future in which they may cease to exist, their daughters and granddaughters living in vastly different worlds far away. Reading about them, I immediately intuit the deep metaphorical connection between their stories and Celine’s, as well as mine: The lives of immigrants, like haenyeo, are lived between two worlds, on the precipice of great cultural loss.

As I write this, I fight the intense urge to take the next plane to Omaha, Nebraska, run home and cradle my mother’s face in my palms. I want to plunge fast into the cold, dark corners of my parents’ basement and excavate all the black and white photos of my grandparents I can find. I want to memorize the images of them wearing matching Mao jackets, serene half-smiles flicked across their faces like calligraphy strokes. I want to bring their histories to the light, archive their legacies and make them mine. I suddenly wish I had the foresight to collect this precious knowledge from them myself, before they died. Doesn’t every child of immigrants feel born into a cultural wealth they know they can never inherit?

As much as I’d like to hold onto a past I’ve never fully grasped, I know I cannot, and it is pointless to try. We tend to tend to think of culture as something static and outside of ourselves, something to be studied, dissected, and preserved. But culture is as alive and breathing as we are. When each memory itself is recalled, it is re-relived and stored as a new memory thereof. That is, every time we think of the past, we imbue it with the present. So too is collective memory constantly remolded and re-remembered by who we are now and who we want to be. Culture is as much about forgetting as remembering, as much about the living as the dead.

When I think of it like that, I realize that my particular variation of identity is as valid and necessary as my mother’s and grandmother’s. There’s no gap between me and them I need to bridge. That gap is our culture, a timeless immigrant way of life all its own. I don’t need to worry about anything else but continuing to move forward and writing my own stories because culture is made by living. The only thing I need to do, the only thing I or anyone can do, is simply exist, and create. How else does anything evolve?

Ironically, reading that these elderly women are experiencing internal conflicts and growing pains so similar to us diaspora youth half the world away actually affords me a richer connectedness to Asia. I can finally relate. All this is what haenyeo means to me. Of course, I have only discovered these thoughts and feelings during my research for “Endlings.”

Before any of that, I was already elated by the mere fact that such a play exists. My heart leapt into my throat as I read the press packet for the show. A story that centers not just one, but three elderly Asian women? In a full production by the prestigious American Repertory Theatre? Even six months ago, I would have thought this completely beyond the realm of possibility.

What little narrative space Asian America is allotted is mostly taken up by the young and assimilated, by stories of how we relate to and define ourselves by whiteness. Rarely do we look in the other direction, Eastward and back. Asian women, especially, seem only allowed to be young and sexualized. Our only acceptable social commentary is to complain about being sexualized. It’s easy for anyone to relate to the anxieties of a pouty 23-year old, or at least project upon her some semblance of humanity. It takes a fuller empathic range to consider the fierce pride of Chinese bottle ladies, or the stalwart beauty of Korea’s elderly mermaids.

When I first saw the photos of haenyo, I too couldn’t help but see these women as foreign bodies, othered in my internalized white gaze. I had to take pause and look again, at eyes and expressions, pressed lips and sidelong glances. Then they came alive, each her own infinite ocean of ambitions, moods, tragedies, and desires. I see a multigenerational past. I see what I might look like when I grow old. I realize, this is the representation I’ve always longed for and never even hoped to see. It is a hunger I didn’t even know existed until it was whetted. This is what “Endlings” means to me.

I had the pleasure of speaking with playwright Celine Song, who is every bit as singular and formidable as her writing. The transcript, edited and condensed for clarity, is below. It is a conversation about beginnings and ends, finding and centering yourself, owning and committing to your voice. “Endlings” premiers February 26, 2019 at the Loeb Drama Center at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA. It is the story of the artist’s final dive into her liminal depths, and the rare, glistening treasures with which she surfaced.

***

Headshot of Celine Song

I just wanted to chat with you about your life and perspective in general, and of course your new play Endlings. I’m really excited to see a production that centers three older Asian women. That never happens.

Yeah, it just never happens. And because it never happens, it’s hard to imagine what it would be like to even see a story about older Asian women. It’s such a specific group, and it’s not just about one of them: I’ve cast all three roles with stunning Asian American actresses.

I was born in Seoul, South Korea. I grew up there, and I emigrated to Canada when I was 12. I lived there for 11 years, and when I was 23 I immigrated again to New York, where I lived until last October. Since then, I’ve been living in LA.

I’ve immigrated twice in my life, and so instead of considering myself a Korean or Canadian or American, I identify mostly as an immigrant. To me, what that means — and immigrants really understand this — is that your family is your hometown. Your family is your home country. I was thinking about that as I wrote this play.

How did you come to write about haenyeo and why?

I watched a documentary with my mom one day, and I just started writing. I quickly realized that this was my first time writing a play about Koreans in any capacity.

How did you decide to go into theater and what has it been like so far as a playwright?

Originally, I wanted to be a screenwriter, but I applied to a few different grad schools in both theater and film, and I ended up getting a call from the head of the playwriting program at Columbia University, Chuck Mee, who convinced me that I should move to New York to become a playwright. I took his advice and moved there a few months later to study with him.

Before Endlings, when I was writing my other plays, I kept having thoughts like “I shouldn’t write plays with old Asian women because they’ll be be hard to cast.” I always felt the need to write plays that were “producible.” Endlings is the first play where I was like: “Fuck you. I’m going to write a play with three old Asian woman in it, and it’s going to have a big cast too.”

That’s awesome! I recently also had that kind of personal change. I studied biology in school because I thought, if I go into the arts I’m never going to be able to make the art I really want. I was doing research for a long time, but a few years ago I was like, “whatever, I don’t give a fuck, I’m going to write. I have a STEM background so I can always make money, but now I’m just doing comedy and writing what I really want and it feels so fucking good. I think for me, it was a matter of getting disenchanted trying to do every other thing. Was there some situation that sparked your change?

Yeah, definitely. My family is actually full of artists. My mom is an illustrator and graphic designer, my dad is a film director and screenwriter, and my little sister is a video game designer and artist. I didn’t want to be a writer for a long time because I saw my parents be freelance artists and it seemed so difficult. Even though my parents were not strict about me pursuing a “normal” career, I was still trying to walk an “easier” path. I actually have a psychology degree, and I studied to be a therapist. That’s not to say being a psychologist is easy — every career is hard in its own way — but there is a lot more certainty in being a psychologist: working hard will reap obvious, direct results.

The hardest part of being an artist is the uncertainty. Even if you do manage to make something good, you don’t know if the world will accept it. So every act of art-making requires a bit of “FUCK YOU” — “I DON’T GIVE A FUCK” — or it would become too difficult spiritually. Especially for Asian Americans, we have seen just too many examples of the world not accepting our voices, erasing them, replacing them. For us, that “FUCK YOU” has to be really strong. Our “FUCK YOU” has to be really passionate to overcome the uncertainty.

At one point, I just said to myself, “I’m going to have to be a writer because it feels like that’s the only thing that makes me happy. It’s the only thing that makes me love life.”

That’s awesome, I feel the same way.

Yeah, it’s the only thing that moves me and that makes me feel something, so I’m going to have to be a writer. Something that was really helpful for me is that when I told my mom, she was like… “Okay. Here’s what we’re going to do.” She had a plan. She helped me apply to grad school in New York and Los Angeles because we were like: “Well, let’s increase the chance of you making it as an artist. Let’s think about this as professionals.” My mom was also like: “I’m going to support you until you’re 40. Until you’re 40, don’t feel like you have to make money, or make something in pursuit of tangible success, because being an artist means you must keep at it whether the world compensates you for it or not. Being an artist means toiling and trying to make things happen until you’re 40.” So in that way, I’m so unbelievably lucky because I know that’s not true for a lot of artists, Asian American or not. My parents will never say: “How much money are you making this month?” They will never make me feel stressed about that. In that way, I feel very lucky.

You said you were writing plays but you were writing plays that were doable. Was there a turning point that made you say “Fuck you I’m going to write what I want”?

I realized that “doable” plays — the kinds with few roles that are interchangeable and can be played by actors of any ethnicity — are by default coded as being for young white people. I was writing these short, tight plays that were under 90 minutes and on one set because that’s the kind of play that really showcases how disciplined the writer is. I was an ESL student who was becoming a writer, and I was so often challenged about my English. I felt extra pressure to prove that I could write a play that was incredibly tight and well-written. I was writing plays that no one could criticize on a technical level. I wasn’t thinking so much about feelings or what the play was doing — I was more concerned with proving to everyone that I was unequivocally an incredible writer, which is really just another way of saying I was writing from a place of insecurity.

Yeah, it’s this double consciousness where you know you’re being judged at a different standard than a white writer. I know exactly what you mean.

Exactly. I was in so many situations where people doubted me. They doubted that I wrote something — like, they’d google the play and be like “oh you’rethe writer”? Or I would be doing these complicated experiments with language, and my actors would think that I was just bad at English. It’s things like that that influenced my work, and I ended up writing these plays defensively, like a fortress against the criticism. Endlingsis the first play where I was not letting myself do that. I was finally allowing myself to write and do whatever I wanted, however I wanted.

This happened because for a few years I had been planning to break up with theater. I had been telling people that this was going to be my last play when I got into the Emerging Writers Group at the Public Theater in NY. I was on the verge of quitting playwriting altogether when I joined that writers’ group, and I told the people who run it, Jesse Alickand Jack Moore, that this was going to be the last play I would write. I wasn’t even sure if I was going to finish it. Jack and Jesse were like “Ok, ok, but keep writing it.” And I was like “I don’t know if I should. It’s impossible to produce.” And they said “Well, let’s talk about that when you finish it.” So I kept writing, and they kept helping me develop it, and we did a final presentation at the Public with a staged reading, and afterward, I remember sitting in the office with Jack and Jesse and crying because I really thought that was it: I thought I had written my last play and that the reading we just did was my last act as a playwright.

And then, not even a week after that, my now-agent, Kevin Lin, who is a brilliant Chinese American agent at CAA, sent me this amazing email at 3am on a Sunday night about Endlings. As an Asian American, and as one of the only POC theater agents in New York, he responded to my play very strongly, and later that week we met and decided to work together. His career began at the A.R.T., and he’s the one who knew Sammi, my director. He is responsible for the production of this play and for my career. He’s the reason I haven’t quit.

Wow, what a story. You also do some TV writing right?

Yeah. I write for a show called Wheel of Time. It’s going to be on Amazon, and it’s a fantasy series sort of like Lord of the Ringsor Game of Thrones. The world is very big, but the room is small: I only work with a few other writers, and everyone is really amazing.I’m having so much fun, and I think our show is going to be really good.

In your experience, what are the main differences between screenwriting and playwriting?

I think the simplest difference is that screenwriting involves less dialogue and more images as a means to tell the story. I also think one needs to approach time and space in screenwriting a bit more literally. In a play, an actor can stand in an empty space and just start speaking. In most films, this would be too strange. A screenwriter is often employed to serve the vision of the director, who is ultimately the primary creator. In the theater, the playwright is king. Her name is usually the first to appear on the marquee. In a play, you can have a teenager play an old lady and a child convincingly, but on screen, a teenager can only play a teenager (most of the time).

Do you prefer one to the other?

I definitely do not prefer one to the other, but I think my screenplays tend to veer a little more in the theatrical direction — at least more than the norm — while my plays remain firmly plays: they are not “cinematic” or “screenplay-like” at all.

Some final thoughts: you mentioned earlier about having the support and guidance of a family of artists. Do you have any advice for young artists, especially Asian American, who don’t necessarily have that support or those networks?

I studied with Anne Bogart in grad school, and this is the most useful advice I have ever received:

- Show up.

- Pay attention.

- Speak from the heart.

- Have no expectations.

For Asian American artists specifically, I would say that it was immensely helpful for me to realize that I could just write whatever I wanted without worrying about what other people wanted or needed from me. I didn’t start writing “Asian plays” because I felt like I should or like I had some duty. I wrote Endlings because it’s exactly what I wanted to do at the time that I did it. The truth is, I’m really proud of the “white plays” I wrote earlier in my career too — those were exactly the plays I wanted to be writing then, and they are also about my soul, not any less than Endlings.

It’s not your responsibility to talk about your “culture” or to be an ambassador — you don’t owe it to other Asians, and you certainly don’t owe it to white people. But if you want to make art about your grandma, why the fuck wouldn’t you? And what are you gonna do? Pretend she’s white? You are who you are, and it is worth remarking on the miracle of that once in a while. You survived the body you live in, in a world that is designed to make you feel low about yourself — that is a triumph that most people do not know. You can talk about that or not talk about that however the hell you want to.

Tickets start at $25 and are available now online at americanrepertorytheater.org, by phone at 617.547.8300, and in person at the Loeb Drama Center Ticket Services Offices (64 Brattle Street, Cambridge). Discounts are available to Subscribers, Members, groups, students, seniors, Blue Star families, EBT card holders, and others.