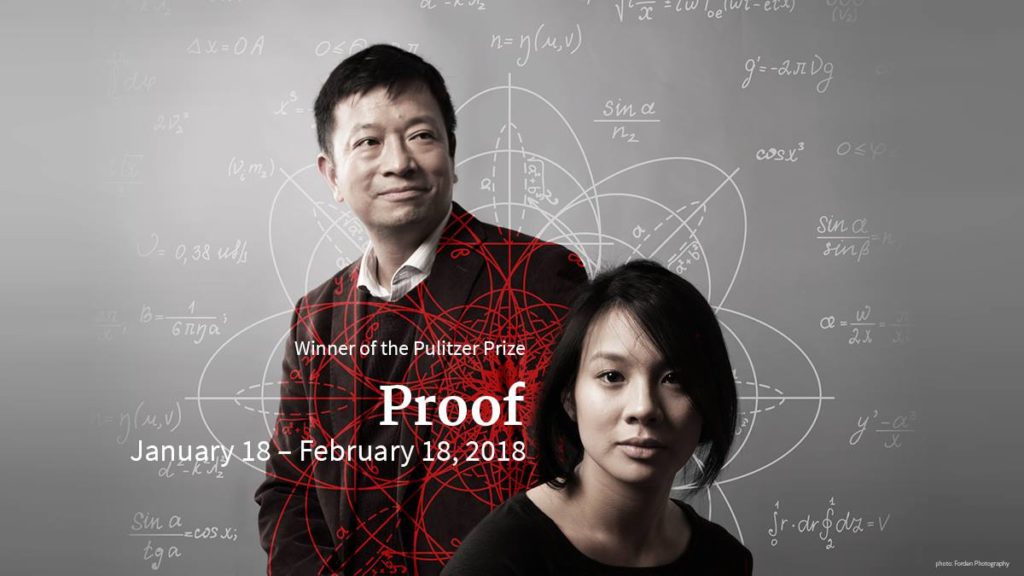

Photo: Forden Photography. Design: Bird Graphics; Featuring Michael Tow & Lisa Nguyen.

Presented by the Nora Theatre Company

Written by David Auburn

Directed by Michelle M. Aguillon

Jan. 18 – Feb. 18, 2018

Central Square Theater

Cambridge, MA

CST on Facebook

Introduction: Below are two pieces in response to The Nora Theatre’s production currently playing at Central Square Theater in Cambridge, MA. First is my critique of the production. The second is an opinionated response from fellow Geek Noelani Kamelamela. I asked Noelani to write a response to the production because representation is important. Three out of four cast members of Proof are Asian-American. This is significant because David Auburn didn’t factor race into his writing process. This means white was his default. No one gets extra credit for treating people of color like human beings. The Nora does get kudos for subverting the racial paradigm.

Review by Kitty Drexel

“In a good proof there is a very high degree of unexpectedness, combined with inevitability and economy. The argument takes so odd and surprising a form; the weapons used seems so childishly simple when compared with the far-reaching consequences; but there is no escape from the conclusions.” – G.H. Hardy, A Mathematician’s Apology

(Cambridge, MA) The stigma around mental illness remains sharp. The Nora Theatre’s production of Proof doesn’t tackle this stigma so much as wait until the audience is pliable and then viciously assault it. It isn’t gentle but it is effective.

Catherine (Lisa Nguyen) is a creative and mathematical genius in a young woman’s body. Her father, mathematics rockstar Robert (Michael Tow), has just died due to fatal complications from an undisclosed mental illness. She is recovering from the trauma of watching her father wither away in her care when PhD student Hal (Avery Bargar) attempts to steal one of her father’s notebooks. They develop an unlikely romance. Claire (Cheryl Daro), Catherine’s sister flies in from NYC to mother Catherine and attend the funeral. The discovery of an extraordinary prime number proof causes great upset.

Auburn’s treatment of potential mental illness is problematic. Doctors, aside from the fictitious Dr. von Heimlich, are shockingly absent from this play. Catherine is never professionally diagnosed but her sister and stalker behave as if they’ve already decided upon a prognosis. Based purely on sexist conjecture and fear from all players, Catherine is manipulated and coerced into believing she’s unsound despite evidence to the contrary. They use her gender as evidence that she’s incapable of intellectual greatness. This is abuse, and bad science. No familial love is so strong that stigma should be embraced.

Ngyuyen and Tow grasp the creative and critical functions dichotomous reality of a scientific mind. They play Catherine and Robert with great sympathy. Nguyen is unenviably realistic. Tow is a spooky but calming presence.

There aren’t really any villains in this production. Everyone is doing the best they can with moderate success; but if there were villains, Bargar and Daro would play them. Hal doesn’t take no for an answer and manipulates Catherine into sex. Claire nags Catherine into depressed silence. Yet, both actors make their characters likable. We are convinced of their good intentions even as they behave horribly.

Proof is occasionally funny but is otherwise a serious play with several dramatic confrontation scenes in which Catherine is forced to defend her intellectual stability. The pivotal dialogues dragged towards the end of the confrontations. The energy stagnates because the scene crests too soon. The actors peak too soon and have nowhere to direct their energy.

Those living with mental illness deserve compassion, representation, comprehensive health care, and respect. Anything less is inhumane. Proof begins a discussion about mental health by implementing math as a catalyst. Auburn’s play isn’t the most knowledgeable of its kind but its existence is helpful.

———————————-

Op-Ed by Noelani Kamelamela

(Cambridge, MA) Central Square Theatre is situated between Central Square and the Charles River on the way to Boston. I happened to walk past recently and was intrigued by a poster for their 2018 season. As someone who identifies as partially Asian, Asian actors on any kind of advertising without a dragon or some calligraphy is rare. At first, I only noticed that the two faces on the poster were of Asian descent.

The play being advertised was Proof, an exploration of what it means to possess both ordinary and extraordinary gifts. A genius father is mourned by his two daughters for the way his mind worked as well as who he was to each of them. Amongst academics, he was exceptional, but both daughters had to live with all sides of him, including his failing mental health. The youngest was keenly interested in his work, and hoped to someday pursue similar aims herself.

Both class and intellectual achievements for all speaking roles are concretely detailed. David Auburn also addresses gender issues as openly as possible. Gender of each person is absolutely essential in this play. The way each character interacts reinforces this, particularly because mathematics as a field is an intellectual setting of the action. There are fewer women than men in the field of mathematics, probably far fewer than there should be. Another key element is that most young men would not be expected to nurse an ailing parent, but a young woman may be encouraged to do so because women frequently are expected to bear the brunt of housework and nurturing labor. Thus, gender cannot be altered.

However, race is not explicitly mentioned in the show. There are no references to skin tones, or foods found outside of the physical setting of the play. There are no references to living outside of the United States of America. In fact, nothing before the father’s generation is discussed. Therefore, one may believe that each person must be an American and Americans can be of any ancestry.

Casting non-white leads has been explored in other productions and Central Square Theatre is especially sensitive to presenting diversity of all kinds in a tasteful manner. I know these things, but I was still worried. I was anxious: perhaps there would be ching-chongy musical cues, ornate Ming vases, maybe some kind of pagoda or terrible kung fu movie accents. As I settled into the first ten minutes, watching Asian actors and side-eyeing the predominantly white audience, my fears dissipated.

Universal themes such as the realities of death and how families could try to assist and nurture ailing, older members take precedence. The set evokes a backyard of any modern American family with some means, though not enough care. Sound and lighting cues are similarly appropriate to the area. Chicago, a place where Asians make up less than 10% of the population, is not truly a character here, though one off-stage confrontation has the potential to irk people of color who have had similar unwanted experiences with the police. Fundamental obstacles which have the potential to delve into culture and custom isn’t offered deeper context but the production sticks to the text and relies on the actors’ strengths individually and as an ensemble.

Although it did not positively or negatively impact the quality of the show, I was pleased by the deliberate casting of Asian leads. For some folks, this version of Proof is the only version they will ever see, and that is not a bad thing, certainly this is a worthy offering and the casting makes sense when considering the bigger picture of the entire show as well as Central Square Theater’s mission. Viewing this presentation can challenge notions audiences may have about who they want to watch and who they consider capable as an actor or team. Production and company staffs around the Boston area may be interested in questioning whether they are deliberately excluding entire racial groups because they lack imagination and conviction. Lastly, If some theatre-goers are put off by the appearance of non-white lead actors: this is good, too. As much as I want to believe that race doesn’t matter in the arts, only people within the arts have the ability to make that statement a reality.