Photos by Eric Antoniou, Boston Lyric Opera 2014.

Presented by Boston Lyric Opera

Music by Frank Martin

Based on Joseph Bédier’s 1900 novel Roman de Tristan et Iseut

New English translation by Hugh Macdonald

Stage Director David Schweizer

Conductor David Angus (Ryan Turner on Nov. 22)

November 19 – 23, 2014

Temple Ohabei Shalom

1187 Beacon Street, Brookline, MA

Boston Lyric Opera on Facebook

Of all the art forms out there, the slowest to adapt to the shifting sands of time is theatre. This is true for many reasons (how long it takes to produce a piece of theatre, how many fingers have to be in the theatre pie, and how many minds have to be shifted about the fundamental precepts of the art form just to name a few…). Some might call this a devotion to tradition; theatre (after all) does have a long and vibrant history to honor at every step of the production process. Others might call it a weakness which, Darwineanly, will be the very demise of the art form if it doesn’t find some way to evolve.

If theatre is slow to change, Operatic innovations move at a glacial pace. The very fiber of Opera is rooted in beautiful, ancient music and the techniques which voices and instruments must use in order to achieve the otherworldly sound quality which the form demands. I think it is because of this necessity for tradition that the other elements of Opera: staging practices, performance practices, and stylistic movement (to name a few) have remained so stagnant through the years.

Boston Lyric Opera is working to shift this paradigm. Their current production of The Love Potion (a piece based upon the ancient story of star-crossed lovers Tristan and Isolt) is untraditional in every sense it can possibly be. It is staged with an eye for dynamic movement and interesting stage pictures. The performers utilize their bodies and faces along with their voices to convey emotion. The sets cry out modern simplicity and anything but the stodgy Victorian sensibilities that the average citizen might associate with stereotypical Opera.

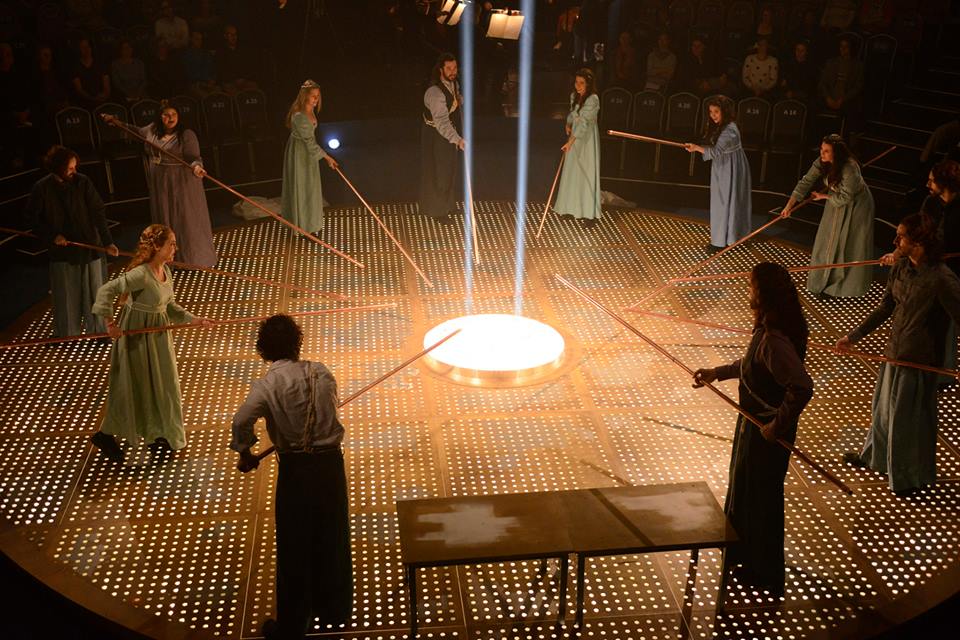

This piece is a part of the BLO Opera Annex series; an initiative designed to present chamber operas fully-staged in “accessible” settings in order to better appeal to a wide audience. Tristan and Isolt is presented at the Brookline temple Ohabei Shalom; and what a gorgeous complement to the programming this space makes. BLO has transformed the temple into a performance space in three quarters with arena-style seating raised above a central performance platform. The careful application of a light hazy smoke allows the lighting (designed by Robert Wierzel) to achieve an eerie almost other-worldly quality. The acoustics of this lofty space create an echo chamber for the voices on display and certainly add to the robust quality of sound that each extremely talented performer brings to the table. In essence: the space really makes this production in a way that it couldn’t possibly be made any other place.

The simple-seeming costumes are elegant and detailed in a fashion which keeps you thinking long after you’ve left the theatre. They serve as a visual metaphor for the story in several subtle and piquant ways which I shan’t spoil here. One thing’s for sure: costume designer Nancy Leary worked every angle she had to create a masterful effect.

While I spent the evening admiring the staging, vocal talent, orchestral talent, lights, and costumes of this production, there was definitely a glaring aspect which didn’t quite live up the splendor of the whole: the material. There is nothing spectacular about the score to this Opera (and I truly mean “nothing”; no arias to speak of, and musically it’s drab and repetitive). In many ways, it’s extremely traditional (I very nearly expected a large woman with a Viking helmet and braids to be singing to me in parts). Because of this adhesion to stereotypical genre tropes with its music, I would not recommend this piece to Opera-beginners. Despite the innovative staging practices, the material just isn’t accessible and will likely scare off anyone curious enough to try but fretful about an adverse reaction to operatic clichés.